“I was at work, and we had just finished our 8 a.m. project meeting with our floor managers,” remembers Cam Ingram, CEO of Road Scholars, the renowned Porsche restoration and sales shop in Durham, North Carolina. “I got a call from my mother, and I thought it was the typical checking-in. She was very emotional. It was a surreal phone call.”

“Get down to the collection!” Ingram’s mother shouted. “There’s been an explosion!”

Ingram and 15 of his employees jumped in cars and roared out of the parking lot. From a distance on Highway 70, they could see black smoke rising. When they reached 111 North Duke Street, the building was aflame. A gas leak from next door had caused an explosion, which set fire to the building the Ingrams owned. Inside was half of the Ingram Collection—one of the world’s most renowned collections of vintage Porsches.

This story originally appeared in Volume 4 of Road & Track.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

“My mom, my dad, my oldest brother, and all my colleagues from Road Scholars had to watch the firefighters as they did their best,” Ingram recalls. “Sadly, a couple individuals lost their lives. That was the most tragic thing.” The family also lost five rare Porsches, and even though an insurance company could write a check, those historic vehicles could never be replaced. They were literally burned off the face of the planet.

On the spectrum of vintage-car investment successes and tragedies, the Ingrams’ fate is unique. But most people who have dabbled in classic cars know how risky and heartbreaking it can be to own a piece of rolling history. For years, we have been reading about vintage cars as a new asset class that has blown the roof off of traditional investing. According to estate and property consultancy Knight Frank, the collector-car asset class appreciated more over the past 10 years than any other collectible except rare whiskey. But it’s easy to forget—when you’re staring at sparkling metal and holding a checkbook—that anything can happen once you’re in possession of that dream car.

To put things in perspective, we collected data, advice from a lawyer, and real stories from car buyers—some of them successes, others far from it.

“My research told me it was undervalued.”

The buyer: Robert Crotty, a software company COO in Los Angeles.

The car: 1969 Ferrari 365 GT 2+2.

When I was fresh out of college, I got a job sweeping floors at a company that would become Fast Cars Ltd., a vintage-car shop in Redondo Beach, just so I could be around the cars. They paid me $8 an hour, and I loved that job. Ever since, I followed the Ferrari market while squirreling away money. In 2014, I was ready to invest. I zeroed in on the 365 GT 2+2 because I wanted a V-12 Ferrari, because it was an Enzo-era car, because I wanted to be able to put my wife and two kids in it, and because my research told me it was undervalued. I had watched earlier Ferraris of the same class grow from $30,000 to $300,000. I believed the 365’s value had room to grow.

I found a car through Fast Cars. It was mechanically solid, the body was beautiful, and it was a perfect color for the design and era, but the interior needed work. One of the things I love to do with cars is improve them, so this seemed perfect, but for the fact that I would have to spend far more than I ever had on a car. Was I scared? Hell yes! When I talked to my wife about buying a 40-plus-year-old six-figure car, she said, “That’s a lot of money. I don’t understand it, but I trust you.” Which was a double-edged sword, because if this went bad, it was all on me.

I bought the car, and driving it was surreal—the power, the sound. I restored the interior back to the original design but with tan leather to complement the exterior color. For four years, I drove that Ferrari all over Southern California, from concours to kids’ soccer matches. We loved that car! Then, while it was on display at the San Marino concours in California, I met two brothers who were looking for a 365. We went back and forth for a couple months until, at a coffee shop in Carmel on the weekend of Pebble Beach, I sold the 365.

Altogether, including the price I paid and the money I spent, I turned a small profit, a bonus on top of having had the pleasure of owning and driving this V-12 Ferrari for years.

“I was freaking out! I wanted to puke!”

The buyer: Kimberly Burroughs, a dentist in Gambrills, Maryland.

The car: 1963 Chevrolet Corvette split window.

In 2018, I saw an ad on Craigslist for a split-window Corvette. I already owned a 1962 Corvette, and I had been looking for a split window, so I traveled to New York to look at it. Everything seemed legit. The guy had a warehouse full of high-end cars—Boss Mustangs, all kinds of stuff. His name was Brian. I gave him a deposit and went back within the next week to get the car.

A friend of mine, also a Corvette owner, looked at it and said to me, “Does the ’63 have this thing in the B-pillar?” We started looking closely at the car, and the more we looked, the more we realized: Something was very wrong. Then we started looking closely at the paperwork. The guy Brian, whom I had bought the car from, had gotten it from this other guy who lived in Connecticut. It turned out the address for the guy in Connecticut did not even exist. Some quick internet searches told us that maybe this guy in Connecticut was a bit unsavory.

I started to panic. We figured out this wasn’t a 1963 Corvette at all; it was a 1964 car with a split window thrown in there. It was perfectly clear from the dash, the console. There are differences: The ’63 has a lot of one-year-only stuff. Everything about this car was fake. The previous owner had even falsified the VIN. I had given this guy Brian $60,000 cash. I called him and said, “Listen, we have a problem. This is not a 1963.” He told me that he didn’t know about it, that his partner had brought this car in. The partner was, of course, in Las Vegas.

It was the worst-case scenario. I called the police. I called my attorney. I called my parents. I was crying my eyes out and wanted to puke, because I’d literally handed a stranger $60,000 in cash.

Amazingly, there is a happy ending to this story. When I finally got in touch with the partner in Vegas, I was able to convince him to give me my money back. Perhaps he did not want to have to deal with the police. Eventually, I did get a real split window. It is sitting in my garage, and I am so thankful to have it.

“The Cobra was always the carrot in front of my nose.”

The buyer: Tom Cotter, author of the Barn Find book series and host of YouTube’s Barn Find Hunter show.

The car: 1965 Shelby Cobra 289.

When I was in the fifth grade, in 1964, a friend gave me a book with pictures of sports cars on the cover. I recognized all except one. What was this Shelby Cobra? I had to find out, and from that day on, the Cobra was always the carrot in front of my nose.

In 2001, I sold my business and was finally ready. I got on the Internet and started searching. When I saw this Cobra for sale in Walnut Creek, California, it was exactly what I wanted. No roll bar, no side pipes, just an original plain-Jane Cobra—just like the one on the book cover when I was a kid.

I went to see it and took it for a 200-mile test drive. Then I called my wife and told her, “This is the one.” I put the phone up to the exhaust pipes and let her hear the rumble. I paid a world-record high price for a Cobra—$167,500. Friends told me I was crazy. Keith Martin, the publisher of Sports Car Market and a longtime friend, thought I paid 20 percent too much. But I had already let friends talk me out of buying a couple Cobras, and I lost them. I didn’t want to lose another.

That May, my friend Peter Egan and I drove the Cobra from California to my home in North Carolina. We drove secondary roads, choosing restaurants and hotels that were as old or older than the car. We lived the life we had dreamed of when we were kids. Peter wrote an article in Road & Track:“Cross-Country Cobra” appears in the February 2002 issue. We went on this dream road trip and took thousands of readers with us.

I have owned CSX2490 for nearly 20 years, and it has taught me something. I’ve owned hundreds of cars, mostly in the $500 range. Any car I’ve ever bought to make money, I’ve broken even at best. Any car I’ve bought from my heart, I’ve enjoyed every minute of ownership.

At one point, five years ago, CSX2490 was probably worth a million, before the market softened. But I am not selling it. My wife and I agreed that if we have to downsize, we’ll move into a smaller home rather than sell the Cobra. To me, it doesn’t matter how much the car has appreciated, because I bought it for love, not for money.

“A little business with my pleasure.”

The owner: Kyle Kinard, Road & Track senior editor living in Seattle.

The car: 1969 Porsche 912

In 2015, I was driving a BMW E30 M3 and watching the Porsche market explode. I had never made a speculative car purchase, but now my idea was to get a little business with my pleasure. I sold my M3 for $20,000, netting a nice profit. You couldn’t get a clean 911 for that money—that ship had sailed. But it was clear the 912 would soon be heir to that bubble. I thought I’d try out this air-cooled Porsche thing and sell for a big profit down the line. The maintenance would be cheap, I thought, because the 912 is essentially a VW engine in a Porsche body.

I did what experts say to do and bought the nicest version of the car I could afford. When this 912 popped up on Craigslist, it was one of the more expensive ones I’d seen. Pristine paint, 60,000 miles. It was past my budget, but I bought it anyway, thinking the due diligence I learned with Eighties BMWs would apply to a Sixties Porsche.

It absolutely did not. Early on, I took the 912 to a Porsche specialist. He clued me in to a bunch of problems specific to the air-cooled world. My stomach dropped. This was way more than I had bargained for. At the time, I was working on the Forza racing game series at Turn 10 Studios outside Seattle. The 912 was a terrible commuter. It didn’t have seatbelts; the heater was barely capable of warming my kneecaps, let alone clearing the windshield. I had to tap dance on the accelerator every morning until the engine caught, then wait for it to stop grumping so I could drive to work. When it rained, the air filters went soggy and choked the carbs. And rain is, shall we say, not uncommon in Seattle.

When I bought the car, the owner presented it as clean and original. He had an immaculate garage, a pristine E-Type on the lift. He and his wife raced Lola T70s in vintage events. I trusted him so much, I made an offer before the test drive. Stupid.

Turns out, the only original thing on my 912 was rust. When I listed it for sale, a prospective buyer (and 911 expert) pulled up the carpet and dug into the layer of black gunk covering the floorboards, imitating the factory coating. The metal beneath was so rusted, I was surprised the seats hadn’t fallen out. One night, the generator died, leaving me stranded on a shoulderless two-lane bridge at midnight in a downpour. SUVs swerved to miss me at the last possible second, over and over.

I sold the 912 after 18 months, for less than half of what I paid for it. I tried to be transparent. I lifted up the carpets and pointed to the rust. The buyer haggled and hemmed and got a great deal, well below market value for even a wonky 912.

But this car wasn’t done with me yet. The guy who bought it would not leave me alone. He kept calling me, complaining, and left me voicemails threatening my health and livelihood. I’ve kept them, in case someone finds me in a ditch someday. On my honor, I pointed out every flaw I knew of when I sold the car. Still, once that Pandora’s Box was opened, there was always something more.

In conclusion: Some thoroughly non-professional advice

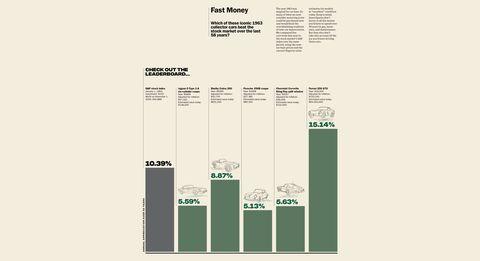

History shows that you’re more likely to earn investing in a boring S&P 500 index fund than all but the most highly appreciating car. But if you do your due diligence, and you buy a car for love and not to make money, chances are you won’t lose.

And what of the Ingram family and their famed Porsche collection? The explosion that destroyed five cars “changed our perspective,” says Cam Ingram. The family spends more time than ever driving their near-priceless Porsches and sharing them with friends.

“I think people sometimes think of classic cars as alternative portfolios,” Ingram says, “instead of thinking, ‘Wow, I can experience life on a whole different level of enjoyment, by using them, by driving them, rather than being focused on how well they have done in value escalation.’”

Stock Models

The first-ever S&P 500–style indices tracking the values of vintage Lamborghinis, Ferraris, Porsches, and more.

The HAGI index is slightly difficult to explain. But its founder, London-based Dietrich Hatlapa, likes to paraphrase Albert Einstein: “If you can’t explain something to a six-year-old, chances are you don’t understand it.” So here’s the HAGI index in a simple sentence: Hatlapa and his colleagues at the Historic Automobile Group International have created an index (a few, actually) that functions like the S&P 500 and can arguably give us today the most data-rich picture of the classic-car marketplace we have ever known.This story goes back to the early 2000s. Hatlapa was a managing director at a major bank called ING Barings. His colleague, Bruce Johnson, was head of research, and part of his work was to help create stock indices for emerging financial markets, where stock trading did not occur on exchanges. It might have taken place in a bar or on a street. So researchers had to figure out how to harvest robust data, then how to use algorithms to track it accurately in an index such as the S&P or Dow Jones. Investors looking into these risky but potentially hugely profitable markets could then have some understanding of the ups and downs.

Hatlapa, originally from Hamburg, Germany,was a classic-car fan. And it occurred to him that the same principle of creating stock indices in emerging financial markets could apply to the classic-car market. There was a lot of anecdotal data on vintage- car sales and some real data such as auction results. But how could he create an index that really put the picture in focus? He partnered with his colleague Bruce Johnson and together they launched HAGI.

“We created what we call a trusted network,” he explains, “whereby we started collecting our data from four sources: dealers, private collectors, marque specialists, and auctions.” How did he get all of that private sales data? By networking and asking for it. “We are 100 percent discreet. The information is for calculating the indices and that’s it. It’s not being resold. It’s totally anonymized. The most important word for us, in terms of how we created this business, is ‘independent.’ We are documenting this market. But we are not involved in it, so we are market-neutral. We do not benefit if it goes up or down.”

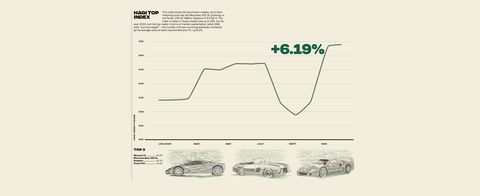

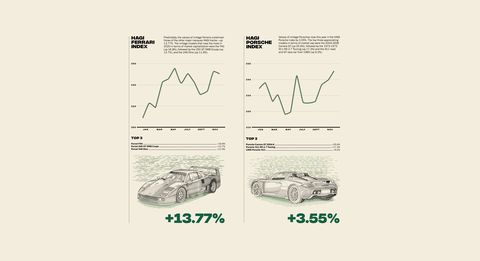

Using a database of over 100,000 sales, Hatlapa and his colleagues created classic- car indices just as they created indices for emerging financial markets. There is one each for Porsche, Ferrari, Lamborghini, Mercedes- Benz, plus a “HAGI Top Index,” which tracks 50 benchmark models from 19 marques in the same way that the S&P tracks 500 companies.

Any questions? Of course there are. How can you track the value of, say, a 300 SL Gullwing when one is in top shape, while another is, for example, rusted and doesn’t have a numbers- matching engine? “We only factor in excellent- condition cars,” says Hatlapa. “If it’s not good, we don’t use it. At the same time, if Stirling Moss ran the Mille Miglia in a certain car, then it is worth double or more. We don’t use that, either, because it skews the picture. This commodity is not 100 percent fungible, the way an ounce of gold equals an ounce of gold. But it’s close.”

How does the algorithm actually work? Now pay attention: The Dow Jones and the S&P 500 behave differently. The Dow is a price index. The stock prices of 30 large companies go up and down, and the Dow tracks them all equivalently. The S&P is a market capitalization index. Each of the 500 companies matters in the overall algorithm according to its market cap, and that is how the HAGI index functions (HAGI calls this “survivor weighting”). Here’s what that means in classic-car terms: Say a Ferrari F40 is worth an average of $1, and 100 survive; that means the market cap—or the survivor weight—is $100. But say the F50 is worth an average of $10, and there’s 1000 of them; the F50’s market cap is $10,000. The F50 thus has far more power to influence the index than the F40.

Do the HAGI indices rise and fall in real time, like the S&P 500? While many of us get a thrill at watching the market move like a speedometer needle, HAGI’s indices are updated monthly. Again: They are modeled after the kind of indices created to track emerging financial markets, and in those (like in the vintage-car market) there are not enough sales by the minute and second to move the market incessantly.

As of our press time for this issue, HAGI had recently released its end-of-year numbers (the indices are available via password on historicautogroup.com). So here is a glimpse at how the market moved in 2020. If the HAGI indices help you make a wise car purchase, send us a photo and we’ll likely publish it on our website in the future.

John Bennett fell in love with cars back when he was a student at Big Sky High School in Missoula, Montana. He still lives there but now has decades of experience as a lawyer in the classic- car transaction field. He’s also a triple-threat Ferrari owner, if you count his 1967 Fiat Dino as a Ferrari (fine by us). We asked Bennett for advice on buying classics, and he obliged.

1

If the seller is European, make sure the title work is “marketable,” meaning that the buyer’s DMV will accept it and will exchange it for a new title, plates, and registration.

2

In 1981, vehicle identification numbers were standardized at 17 digits. A car made before 1981 may not have a 17-digit VIN. That means you can’t run a Carfax (or equivalent) search as part of your due diligence. If this is the case: a) run the VIN through U.S. law enforcement to confirm that the car hasn’t been reported stolen, and b) get a copy of the title from the seller, and then contact the U.S. DMV that issued that title to make sure that the title is the last one that a DMV issued.

3

When ready to buy a car, get a purchase contract (which is not the same as a bill of sale) in writing. It should contain all of the terms of the deal, and it should allow the buyer to examine the car and still be able to get out of the deal if the buyer isn’t satisfied with the condition.

4

If the buyer is not a marque expert, he or she should seriously consider hiring one to a) examine the car, b) assist in determining the car’s value, and c) assist in negotiating the price. A marque specialist may seem like an expensive addition to the vehicle cost, but this could save you volumes in the end.

5

While it may seem obvious, for work on the car use a shop that specializes in that marque and has a good reputation. Ask around!

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES