Oral health in long-term care has been a long-standing challenge for dental professionals. As I explore this space, I have found that caregivers are sometimes unfairly blamed for the poor oral conditions that are seen in dependent populations. There have been multiple great caregiver training and collaborative programs that have ultimately failed due to lack of funding and/or caregiver turnover. In light of these programs falling short of solving the problem, what if we shift our thinking? What if we stop relying on caregivers and take it upon ourselves to ensure that oral hygiene services are being provided? As leaders in oral health, we need to drive these programs down a more sustainable path that will lead to better oral health for dependent populations. Instead of reinventing the wheel, perhaps we need a new driver.

It is this type of thinking that led us to develop various methods that place the dental professional in the driver’s seat. In this article we will discuss: our assisted and guided oral hygiene programs, what we use for these programs, and a documentation system designed specifically to provide oral hygiene assistance for dependent and semidependent populations.

Assisted oral hygiene

In collaboration with a work group consisting of members from Your Special Smiles PLLC (Jingjing Qian, RDH-EA, and myself), a consultant (Paul Glassman, DDS, MA, MBA), faculty from Idaho State University Dental Hygiene Sciences (Rachelle Williams, MS, RDH-EA, and Ellen Rogo, PhD, RDH), and the leadership of the Idaho Oral Health Program (Kelli Broyles, RDH-EA, and Matt Zaborowski, MPH, CPH), we have defined assisted oral hygiene as:

Physical assistance with oral hygiene procedures for individuals who are unable to adequately perform their recommended self-care oral hygiene regimen. Assisted oral hygiene is a specific service and may be delivered separately or as part of a remote oral health support program.

It is important to note that these definitions are working definitions that we have developed to facilitate communication and disseminate information. They have not been made official by dental authorities outside our work group.

Proper oral hygiene is not always a simple task. Think about trying to get a large man who has violent outbursts to brush his teeth when he does not want to. What about a 97-year-old woman who has dementia, cannot drink thin liquids, and does not like people touching her face? The idea that oral hygiene is simple, and that it “only takes two minutes,” assumes complete cooperation, no conversation, and no infection control protocols. We have found a more realistic estimate of the time to provide adequate oral hygiene for a dependent or semidependent adult to be 15–20 minutes per individual.

If this responsibility is placed on a caregiver, that person would spend up to 10 hours per day providing oral hygiene for a 30-resident facility. See how this may be an unrealistic expectation based on time alone?

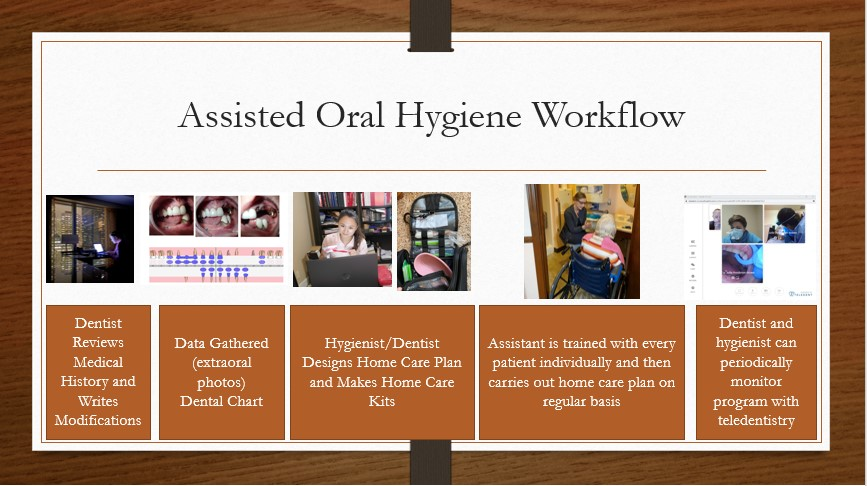

Figure 1: Workflow for assisted oral hygieneIn our assisted oral hygiene program, we provide dental team members who can focus their time and energy exclusively on oral hygiene for participating residents. Various structures can be created to carry out such a program. The following describes how our program is structured and each team member’s responsibilities.

Figure 1: Workflow for assisted oral hygieneIn our assisted oral hygiene program, we provide dental team members who can focus their time and energy exclusively on oral hygiene for participating residents. Various structures can be created to carry out such a program. The following describes how our program is structured and each team member’s responsibilities.

Dentist responsibilities: The dentist reviews the resident’s medical history and determines if any modifications are needed in the provision of oral hygiene. Medical or behavioral consultations may be necessary. Live interaction with residents may be needed. The dentist gives the hygienist this information in order to develop a safe and effective hygiene plan. The dentist periodically monitors the program using teledentistry or in-person interactions.

Hygienist responsibilities: The hygienist uses information from the dentist along with photos, videos, and live interactions to determine the products needed. A formal hygiene plan is then written for each resident. The hygienist trains the assistant to carry out the hygiene plan. The hygienist monitors the program using teledentistry or in-person interactions.

Oral hygiene assistant responsibilities: The oral hygiene assistant learns the specific hygiene plan for each resident from the hygienist and carries out that plan under the direct visual supervision of the dentist or hygienist. The dentist or hygienist determines when the assistant is capable of independently providing these services for each resident. It is important to note that some residents may present unique challenges that require a longer period of supervision. After the oral hygiene assistant is working more independently, the dentist or hygienist continues to check in periodically through in-person interaction or teledentistry.

Figure 2: Ms. Savanna Hendren, our first oral hygiene assistant, was key in the successful development of this program. She was a dental hygiene student at the College of Southern Idaho during her time with us.We have determined these roles to maximize safety and minimize cost to families/payers. Each member of the team has a meaningful responsibility for which they are trained. Figure 1 illustrates our workflow. Figure 2 demonstrates the program in action.

Figure 2: Ms. Savanna Hendren, our first oral hygiene assistant, was key in the successful development of this program. She was a dental hygiene student at the College of Southern Idaho during her time with us.We have determined these roles to maximize safety and minimize cost to families/payers. Each member of the team has a meaningful responsibility for which they are trained. Figure 1 illustrates our workflow. Figure 2 demonstrates the program in action.

Guided oral hygiene

We had an assisted oral hygiene pilot program up and running, and we were making a difference for the participants. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Facilities went on lockdown, and we were locked out. Oral health was still important, but the risks we posed at that point were possibly greater than the benefits. We were forced to pivot; we needed someone “on the inside” to carry out the physical aspect of our program. We decided to turn back to the caregivers, but this time, we were going to do it off the clock. We also utilized synchronous teledentistry.

In shifting oral hygiene responsibility to the caregivers, we knew that if we tried to add responsibility to their already busy shifts, we would be right back where we started. Instead, we offered to partner with the facility/caregivers to provide oral hygiene outside of their normal shifts. Grant funding was given to the facilities to help cover the cost of the additional hours.

As the pandemic progressed and facilities began to experience more staffing issues, our oral hygiene program started to create overtime problems. These were solved by using grant funds to directly pay the caregivers as subcontractors. The caregivers would then carry out the oral hygiene plan while engaging in synchronous teledentistry with our hygienist and oral hygiene assistant.

We felt this process needed a name, so our work group developed the term guided oral hygiene to describe this system and defined it this way:

Utilizing audio and video technology to guide a patient or caregiv

er as they carry out self-care oral hygiene on a regularly scheduled basis. Guided oral hygiene is patient-specific and does not apply to the use of generic prerecorded oral hygiene instruction videos. Guided oral hygiene is a specific service and may be delivered separately or as part of a remote oral health support program. Guided oral hygiene can be represented by a combination of OHI (D1330) and synchronous teledentistry (D9995).

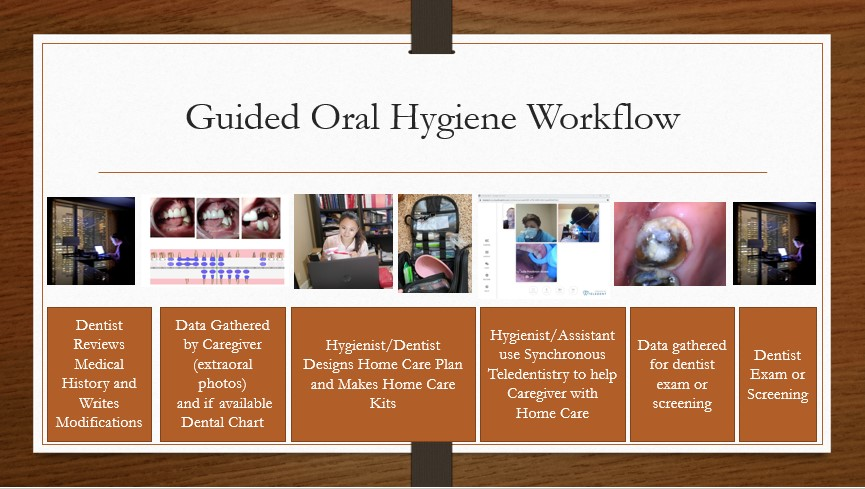

Figure 3: Workflow for guided oral hygieneThis is our structure for a guided oral hygiene program:

Figure 3: Workflow for guided oral hygieneThis is our structure for a guided oral hygiene program:

Dentist responsibilities: Same responsibilities as in the assisted oral hygiene program.

Hygienist responsibilities: Same responsibilities as in the assisted oral hygiene program.

Oral hygiene assistant responsibilities: Instead of providing hands-on care, this person will guide caregivers or residents in providing oral hygiene utilizing synchronous teledentistry on a regular basis. The assistant will only do this after a period of direct supervision with the dentist or hygienist. The plan and/or any changes will be created and approved by the hygienist and/or dentist. In some cases, the hygienist will take on this role. This decision will be made by the dentist and will be based on patient complexity and team member training.

Caregiver responsibilities: The caregiver follows the synchronous teledentistry instructions given by the oral hygiene assistant or hygienist.

Figure 4: Jingjing Qian, RDH-EA, met Carolina Lopez, CNA, in the parking lot to teach her oral photography and dental terminology.Just as in assisted oral hygiene, every member of this team carries out an important role in this system. Figure 3 illustrates our guided oral hygiene workflow. Figures 4–6 demonstrate the program in action.

Figure 4: Jingjing Qian, RDH-EA, met Carolina Lopez, CNA, in the parking lot to teach her oral photography and dental terminology.Just as in assisted oral hygiene, every member of this team carries out an important role in this system. Figure 3 illustrates our guided oral hygiene workflow. Figures 4–6 demonstrate the program in action.

Potential future uses for each system

When we look at these two systems, we can see that they each serve a purpose. During a pandemic, it is important to minimize the number of people going in and out of a facility. In this circumstance, guided oral hygiene is the safest option. It may also be applicable during flu season or other phasic communicable diseases that pose a risk for our vulnerable populations.

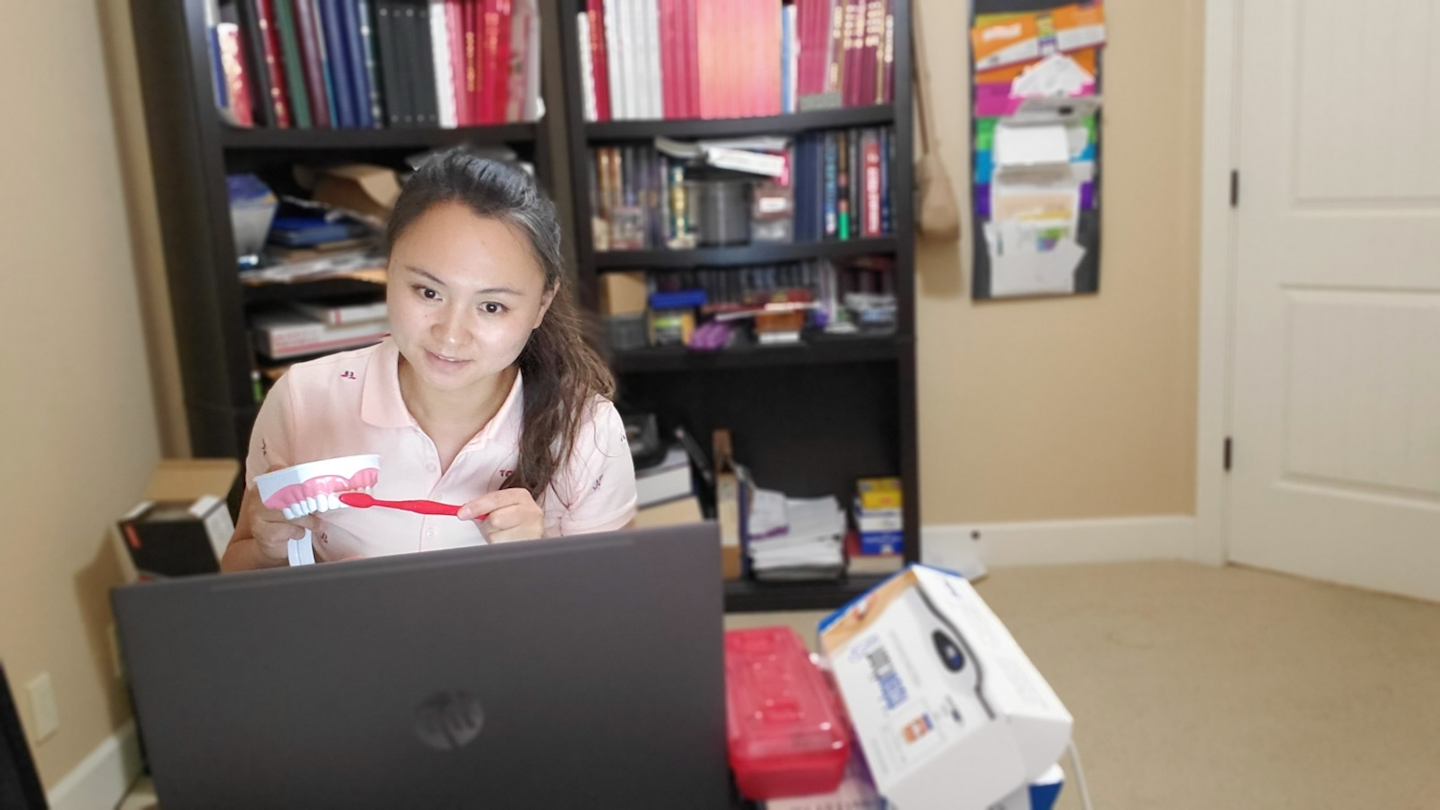

Guided oral hygiene may be the most efficient system in other situations as well, such as when a facility is geographically difficult to access, there are too few  Figure 5: Jingjing Qian, RDH-EA, uses a model to demonstrate oral hygiene techniques while participating in a guided oral hygiene session.residents to attract and train an oral hygiene assistant, or for dependent adults who rely on a caregiver in their private home.

Figure 5: Jingjing Qian, RDH-EA, uses a model to demonstrate oral hygiene techniques while participating in a guided oral hygiene session.residents to attract and train an oral hygiene assistant, or for dependent adults who rely on a caregiver in their private home.

These programs can be combined in various ways. For example, guided oral hygiene can be used to periodically monitor an assisted oral hygiene program. Guided oral hygiene is more expensive to administer as it involves more paid team members providing the same service; assisted oral hygiene may be more affordable in ordinary circumstances. It is our goal that all dependent and semidependent patients have access to this type of service in the future.

Tech considerations

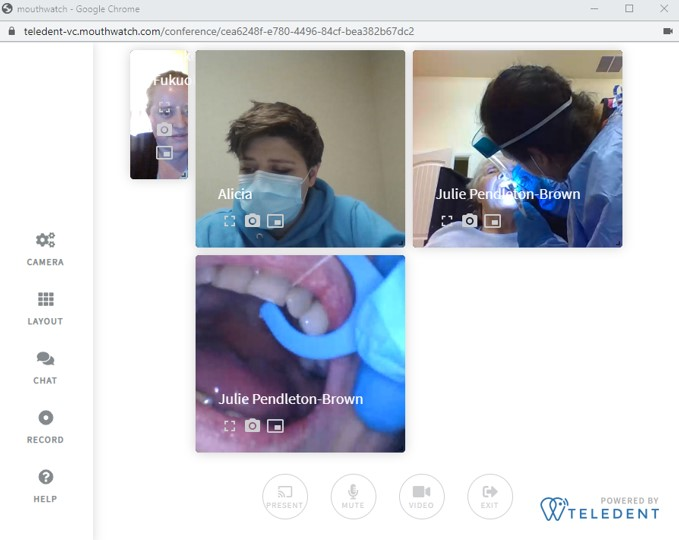

When selecting technology, important considerations are affordability, HIPAA compliance, user support, and internet connection. Wi-Fi connections and security  Figure 6: A screenshot of Alicia McMurtry, our oral hygiene assistant. She is explaining to Maria Santana, CNA, about how to use a flosser.settings in long-term care are not all the same. Our program provides guided oral hygiene services in two different facilities. In one facility we struggle with Wi-Fi connection and in the other, log-in security and site blockage. When testing teledentistry platforms, it is important to put them all on the same playing field. Test them from the same location using the same internet, and then test them all again in a new location using Wi-Fi.

Figure 6: A screenshot of Alicia McMurtry, our oral hygiene assistant. She is explaining to Maria Santana, CNA, about how to use a flosser.settings in long-term care are not all the same. Our program provides guided oral hygiene services in two different facilities. In one facility we struggle with Wi-Fi connection and in the other, log-in security and site blockage. When testing teledentistry platforms, it is important to put them all on the same playing field. Test them from the same location using the same internet, and then test them all again in a new location using Wi-Fi.

Looking at HIPAA compliance, it is important to consider that even though regulations were relaxed during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to set up a system that will be in compliance over the long term. Learning a new system takes time, and it is not desirable to have to learn it twice. When implementing a system, realize that people have various levels of technological expertise. It is a good idea to set expectations for the first few sessions such that they accommodate troubleshooting unexpected challenges.

We use Lester Dine extraoral cameras, MouthWatch intraoral cameras, and the MouthWatch TeleDent platform. In one of our facilities, we use a MiFi personal hot spot device to account for the lack of adequate Wi-Fi.

Tools—common and nontraditional

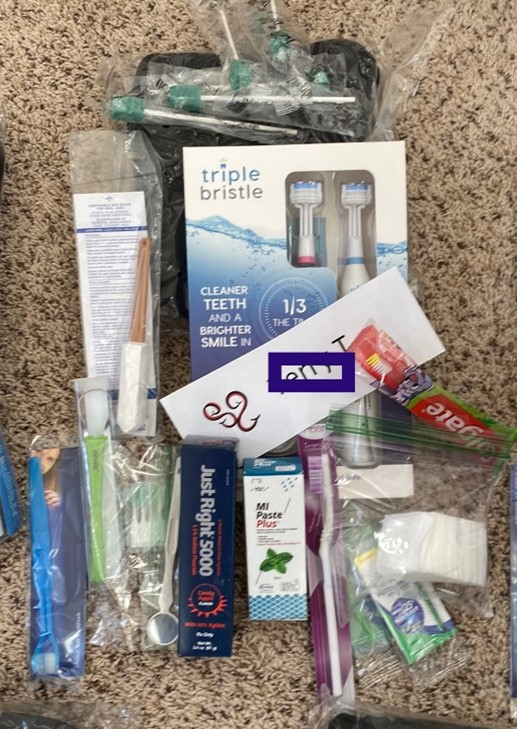

Our kits (figure 7) are customized for each resident, but they also take into consideration caregiver safety. When selecting oral hygiene tools, ask the following questions: Will the tool break if the resident bites it? Does using the tool necessitate that caregivers put their fingers where they could get bitten? Is there potential for the resident to swallow all or part of the tool?

Figure 7: These are some of the oral hygiene tools we provide for the residents. Each kit is customized to the resident’s needs and desires.Some nontraditional items that have been found to be particularly useful are adult bibs, lip balm, sunglasses, emesis basins, handled bite blocks, a single photography cheek retractor, and toiletries bags. We also discovered that the MouthWatch intraoral camera can be used both as a tool for teledentistry and as a light source for the caregiver to see into the posterior of the mouth.

Figure 7: These are some of the oral hygiene tools we provide for the residents. Each kit is customized to the resident’s needs and desires.Some nontraditional items that have been found to be particularly useful are adult bibs, lip balm, sunglasses, emesis basins, handled bite blocks, a single photography cheek retractor, and toiletries bags. We also discovered that the MouthWatch intraoral camera can be used both as a tool for teledentistry and as a light source for the caregiver to see into the posterior of the mouth.

Toothpaste and mouthwash are customized based on patient needs. With the

variety of products used in our programs, some might be seen as unique combinations. For residents who would benefit from a chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash but are unable to swish and spit, a local pharmacy compounds a 0.12% chlorhexidine gel. The oral hygiene assistant can apply the gel to the teeth and gums with a sponge or a gloved finger.

For residents who will swallow anything that is put in their mouth, we consider brushing each quadrant using fluoride-free or low-fluoride MI paste. Then, at the end of the regimen, we use the Just Right 5000 ppm fluoride paste from Elevate Oral Care as a topical fluoride treatment. This product has a dosed pump so the caregiver can apply a more predictable and safer amount of fluoride. We instruct caregivers to dry the teeth with a 2×2 gauze, take a single dose from the pump on their finger, and wipe it across the facials of the teeth.

Finding the right toothbrush(es) for each resident also takes time, trial, and error. While each brush has its own advantage, we consider a Nano brush for those who have friable gingiva. It has over 10,000 bristles and is very soft. For those with a significant gag reflex, a child-size brush might be best. For those with limited cooperation, we consider the Triple Bristle three-sided ultrasonic brush. If the ultrasonic vibrations further decrease cooperation, a manual three-sided brush—such as the Surround Brush, the Collis Curve, or Dentek—may be used. We also use various other electric and manual brushes as the situation requires.

Interproximal cleaning is important, but sometimes flossers are difficult to use or can’t be used due to patient safety considerations. Various interproximal brushes and picks are available based on individual needs. For patients who are able to tolerate irrigation, the Waterpik combined with an emesis basin and adult bib can be very helpful. The corded Waterpik has a larger basin that won’t need a refill, but the cordless one can be used in the shower to decrease potential mess.

Color-coded documentation

There are various ways to document the provision of assisted oral hygiene and guided oral hygiene services. The Your Special Smiles Oral Hygiene Ability Spectrum was developed to encourage independence, but also to provide help where needed. This is a color-coded documentation system that can show progression or regression as well as document challenges that may be presented in this setting. In this system, residents can fall into one of seven categories:

- Independent (purple): Residents who fall into this category are able to perform their entire recommended oral hygiene regimen by themselves, and they do well. For these residents, we regularly document that we checked to make sure they are doing well and have the supplies they need.

- Motivation needed (blue): Residents who fall into this category are able to perform their entire recommended oral hygiene regimen by themselves, but they need someone to remind them to do all or parts of the regimen. For this, we document the reminders and that they have the supplies they need.

- Limited assistance needed cooperative (green): Residents who fall into this category are able to perform parts of their recommended oral hygiene regimen themselves, but they require help in other parts. They willingly accept help. For this, we document the help that was a given and that they have the supplies they need.

- Limited assistance needed semicooperative (yellow): Residents who fall into this category are able to perform parts of their recommended oral hygiene regimen themselves but require help in other parts. They often do not willingly accept help in one or more area. For this, we document the help that was given, where they struggle, and that they have the supplies they need.

- Dependent cooperative (orange): Residents who fall into this category are not able to perform their recommended oral hygiene regimen, but they will allow the caregiver to do so. For this, we document the help that was given and that they have the supplies they need.

- Dependent semicooperative (pink): Residents who fall into this category need assistance with oral hygiene and are somewhat cooperative with caregiver assistance. Perhaps they will allow brushing, but they may not be cooperative with flossing. For this, we document both successes and failures and that they have the supplies they need.

- Dependent noncooperative (red): Residents who fall into this category need assistance with their recommended hygiene regimen and are not cooperative or completely refuse oral hygiene assistance. For this, we document efforts made in behavior management programs such as modifications tried, desensitization plans, and other ways we plan to improve the resident’s oral health.

Residents can move up and down on this scale. Using this system, we can chart the resident’s progression or regression. Documentation also shows the caregiver’s efforts. Health-care providers, facility administrators, and families can see if oral hygiene outcomes are due to lack of effort or lack of cooperation. This system also encourages troubleshooting and persistence, as failed efforts are documented and followed by alternative approach strategies (which are also documented).

The system promotes independence. Striving for independence is very important in this population. The more independent a resident can be, the better for all parties involved. The pandemic has demonstrated that challenges do arise. Sometimes staffing for this system is not possible, even in the best of places with the best of intentions.

For free, downloadable YSS Oral Hygiene Ability Spectrum Forms, visit our website at yourspecialsmiles.com/handouts-and-documents.

Conclusion

It is considered common knowledge that basic home hygiene helps prevent oral disease. What is not common knowledge is the challenges that exist when providing basic home hygiene for dependent adults. Through assisted oral hygiene, guided oral hygiene, and a detailed documentation system, together we can improve the oral health of this very deserving population.

Author’s note: This paper was written based on our own experiences and lessons learned from our developing programs. For that reason, we do not have specific references. This article is not intended to be seen as evidence-based dental research, but rather, a practical approach to solving a common problem. We realize that anecdotal information is the lowest form of evidence, and we look forward to those who can quantify findings from programs such as these and show that they are effective. We know our colleagues at Idaho State University are working on this, and others may be as well. We cheer you all on, and we will value your data.

Author’s disclosures and conflicts of interest:

- Recipient of HRSA Grant. “This project was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of the financial assistance award totaling $569,295 with 70% funded by HRSA/HHS and $169,295 and 30% funded by nongovernmental source(s). The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, HRSA/HHS or the U.S. Government.”

- Though Dr. Fukuoka has no direct financial relationship with any companies, she has given courses sponsored by Elevate Oral Care and MouthWatch for which she has had travel expenses funded and received honoraria.

- Various companies, such as Triple Bristle and Waterpik, have donated products or given discounts to benefit our programs.

- A special thank-you to Kelli Broyles, RDH-EA, for helping edit this document.

Editor’s note: This arti

cle first appeared in Through the Loupes newsletter, a publication of the Endeavor Business Media Dental Group. Read more articles and subscribe to Through the Loupes.

Brooke MO Fukuoka, DMD, FSCD, is a dentist in rural Idaho who has a passion for improving oral health for adults with disabilities and adults living in long-term care. She owns a part-time mobile/teledental/hospital practice, Your Special Smiles PLLC. She also works at a federally qualified health center, Family Health Services. Together with this health center, Dr. Fukuoka is developing an advanced delivery dental clinic for adults who have special health-care needs.

Brooke MO Fukuoka, DMD, FSCD, is a dentist in rural Idaho who has a passion for improving oral health for adults with disabilities and adults living in long-term care. She owns a part-time mobile/teledental/hospital practice, Your Special Smiles PLLC. She also works at a federally qualified health center, Family Health Services. Together with this health center, Dr. Fukuoka is developing an advanced delivery dental clinic for adults who have special health-care needs.