Since last March, one sentence has been looping endlessly on the ticker tape in Bree LeMay’s brain: What the fuck is going on right now. It’s not really a question but a mantra, an all-purpose reaction to a year of being marooned in a 1,200-square-foot apartment with a toddler, a prepubescent boy and no dishwasher.

The mothers, in general, are not all right, and single working mothers such as Bree have disproportionately borne the psychic and economic brunt of the pandemic. Overnight, she and many of the roughly 15 million other single mothers in the U.S. watched their already precarious safety nets disappear — their childcare routines, their incomes, any sense they might have had of being in control of their lives.

The pandemic has undone generations of progress for women in the workforce. In the months leading up to the pandemic, there were more employed women than men for the first time in modern U.S. history, according to the Center for American Progress. Now the number of working women is on par with 1980s levels of labor force participation.

Those losses are partly the result of the pandemic’s outsize impact on the industries in which women, particularly women of color, were already overrepresented, including the service, hospitality and home health sectors. But in many cases, the loss of school and daycare programs has forced women out of their jobs; others have left their careers from exhaustion, worn down by months of juggling their roles as employees, parents and homeschool monitors.

The disparities in employment among women and men came into sharp relief last fall, when the school year resumed in hybrid fashion. For parents of young children, especially, this arrangement requires someone to stay at home with the kids on remote learning days — and that someone, overwhelmingly, is a female caregiver. Research from the Center for American Progress shows that in September, women dropped out of the workforce at four times the rate of men. Since November, 73 percent of the Vermonters who have lost or left their jobs are women; nationally, single mothers have dropped out of the workforce at a rate of 9 percent, the greatest decline among all groups of parents.

These statistics hint at the deep-rooted gender inequities that the pandemic has forced into the open — the fundamental disconnect between what society demands of women and how it fails to support them. In that gulf, women are drowning. In a July 2020 poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 69 percent of mothers said their physical health has suffered due to worry and stress during the pandemic, compared to 51 percent of fathers.

In response to this growing economic and mental health crisis, a coalition of more than 50 prominent women, including celebrities Amy Schumer, Charlize Theron and Gabrielle Union, bought a full-page ad in the New York Times in January, calling on President Joe Biden’s administration to adopt a “Marshall Plan for Moms.” The proposal, introduced last month in the U.S. House of Representatives by Rep. Grace Meng (D-N.Y.), outlines a set of broad reforms — including expanded paid family leave, affordable childcare and direct payments to mothers — aimed at addressing the underlying conditions that have left women most vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic. Some of those priorities are reflected in Biden’s $1.9 trillion relief package, which would provide monthly payments of up to $300 to most families with children and $15 billion to help offset the cost of childcare for low-income parents. The legislation is expected to be approved in a final congressional vote on Wednesday.

In normal times, the work of being a mother is exhausting and mostly invisible, an endless loop of emotional and physical tasks that resets itself daily. In a pandemic, that work has been isolating in ways that have pushed many women to the brink. For three single mothers in Vermont — Bree LeMay, Sara Verdery and Betsy Hibbitts — life during COVID-19 has been a year of unimaginable exhaustion and angst, of rage and regret. Of holding it together, somehow, while everything else is falling apart.

Spring 2020

Bree

Before the pandemic, 40-year-old Bree LeMay had a system for managing the high-wire act of single working motherhood. Four mornings a week, she sent her fourth grader, Niah, on his walk to Integrated Arts Academy, less than two blocks from their rented apartment at the Bright Street Co-Op in Burlington. She dropped off her 2-year-old daughter, Imaan, at daycare in the South End, and then went to work as a hair stylist at O’M Salon on Main Street until 5 or so, when she picked up Imaan from daycare and Niah from his afterschool program at the Boys & Girls Club.

Then, last March, the pandemic arrived. Bree remembers the slow, steady drip of bad news, the sensation of watching movie online or watchartoononline her life unravel by degrees. First, K-12 schools were dismissed, then childcare centers had to close. By the time salons and other close-contact businesses were ordered to shut down on March 21, Bree, stuck at home with an antsy 9-year-old, a 2-year old who was still nursing, and virtually no income, had entered total panic mode.

Bree has always been a single parent, and she was used to being everything to her children. But homeschooling added a new kind of pressure. “I am not supposed to be my son’s teacher,” Bree said. “I’m supposed to be his safe zone, the person he comes to for advice and comfort.”

Surrounded by the distractions of home — his anime action figures, television, the infinite possibilities of YouTube — Niah struggled to focus on school. When Bree pushed him to do his work, Niah pushed back, usually by rolling his eyes or unleashing a long, guttural Uuuuuugh. Multiple times a day, Bree tried to explain to him that he had to finish his assignments before he could chill out, that he couldn’t see his friends because of the germs. He was sad and angry at the sudden loss of his social life, and Bree felt trapped in the role of enforcing rules that made him miserable.

Bree was miserable, too. She existed in a sleep-deprived haze; every day was simultaneously a fresh crisis and exactly the same as the one before. She had always been a worst-case-scenario thinker, but none of the possible catastrophes she’d imagined involved being indefinitely unemployed because of a global pandemic. Friends and family stepped in to help her financially and logistically, which took some of the edge off her anxiety. People shopped for her so she wouldn’t have to drag Niah and Imaan to the grocery store; others sent her gift cards for food.

Meanwhile, Imaan clung perpetually to Bree’s body. If Bree sat on the couch, Imaan climbed onto her lap. If Bree tried to move her away, Imaan flailed and screeched. This was especially not ideal during the multi-week stretch in May when Bree was trying to get through to the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance Hotline, an experience that made her feel like she was living in the world’s most demoralizing video game. Every day, she called the number over and over again, dozens of times an hour, dressed in her sweats and slippers and bathrobe, Imaan hanging from her nipple.

Sometimes, she got to an automated message that she hadn’t reached before and rejoiced, only to be spontaneously disconnected. One day, she called the hotline more than 100 times. By the time she finally managed to get her application approved, which allowed her to recoup all the income she’d lost — some $10,000, by her estimate — it felt, she said, like a fucking miracle.

Sara

In the earliest days of the pandemic, before the coronavirus had reached Vermont, Sara Verdery heard an NPR interview with a reporter in Portland, Ore., where the virus had just forced the city into a lockdown. The NPR host asked what the rest of the country should expect in the weeks to come, what it felt like to have your world suddenly shrink to the dimensions of your domestic habitat. As Sara remembers it, the reporter said: “Get ready to pack and unpack the most extreme stress and anxiety you’ve ever experienced in your life, multiple times a day.”

For Sara, the packing and unpacking happened slowly. Her husband was considered an essential employee at his factory job, so while he was gone during the day, Sara was home in their apartment in Burlington, toggling between remote work and organizing a homeschooling routine for their 4-year-old daughter, Edith. Sara, 37, was a behavioral interventionist at Mosaic Learning Center, a school in Colchester for students with special needs, and throughout the spring, she managed the collision of her work and home lives by relegating her job to the margins of her day. Each morning, she set up Edith with “Sesame Street” during her 8 a.m. Zoom call with the student she mentored, then she would devote the rest of the day to the learning schedule she had created for Edith.

The teacher role came naturally to Sara, and she leaned into it hard. She ordered a massive calendar, which she used to teach Edith the names of the months and days of the week, and a kiddie weather station, which they consulted each day to figure out what to wear on their afternoon walk. Sara squeezed in the rest of her work for Mosaic in the evenings, when her husband came back from his shift.

As Sara scrambled to keep Edith fed and entertained and on track with her lessons (while somehow, improbably, managing her own workload), she began to experience her husband’s absence as something bigger, a symptom of a fundamental imbalance in their relationship. Whenever Edith got sick, it was a foregone conclusion that Sara would miss a day of work to take care of her; when Edith entered preschool, Sara was the one who always made sure Edith had cards for her classmates on Valentine’s Day. “I feel like the women of our generation were taught to be strong and independent, but all the sons were still babied,” Sara said. “And what our mothers were teaching us, they weren’t practicing. So we didn’t see it, and we never learned how to demand it.”

As the months of quarantine wore on, it began to dawn on Sara that she felt more relaxed, more herself, when it was just her and Edith. She simultaneously resented her husband for being gone and longed for him to leave.

Betsy

The first two months of the pandemic shutdown were absolute bliss for Betsy Hibbitts. For years, she’d been desperate for a sabbatical, a forced state of hermitage in which she could finally reflect on parts of her life that the chaos of recent years had not allowed her to process: the death of her father, the fire that destroyed her first house.

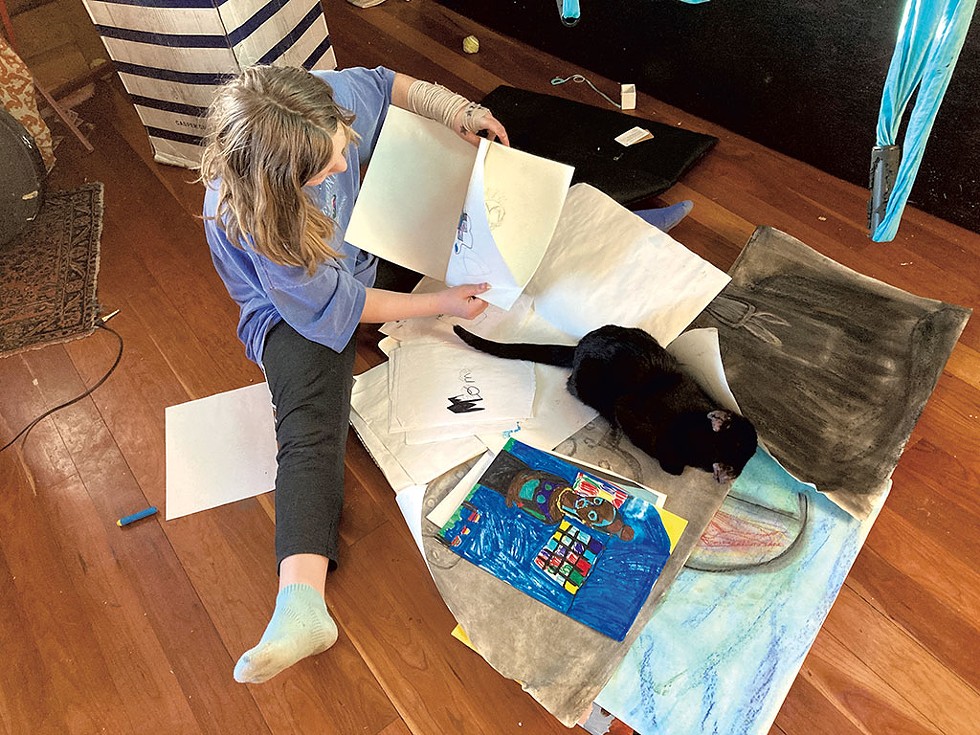

Now, the virus shutdown had eliminated the daily commute to her job in Burlington as a public defender. With court hearings on hold, work slowed down. Her daughter, Destiny, a fifth grader at Christ the King School in Burlington, missed seeing her friends, but she was also an artistic, self-sufficient kid, content to sit in her room by herself, drawing and painting and doing her online schoolwork.

Before Betsy was Destiny’s mother, she was her lawyer. In 2015, Betsy represented Destiny and her two siblings in an abuse-and-neglect case. Their biological mother was in the throes of a heroin addiction, and the state had removed the children from her custody. Destiny, then 4 years old, was sent to live with her father, whom she barely knew. Three months later, he brought her to the Burlington Police Department, told the officer on duty that he didn’t want her anymore and left.

One foster care situation after another fell apart, and on the morning of Betsy’s 46th birthday, she found herself standing in the parking lot of Shelburne Vineyard with a screaming, sobbing Destiny, who had just been offloaded by yet another adult. Betsy saw Destiny’s animal pain, and she recognized that this child couldn’t handle another abandonment.

Betsy lived alone; she had no children, nor did she plan to raise one, not even when she decided, then and there, to take Destiny home to her farm in Ferrisburgh. Legally, she wasn’t supposed to house her own client, but she got special approval to become Destiny’s foster parent. Almost immediately, Destiny started calling her Mom. After a three-year legal process, Betsy became her adoptive mother in 2018.

Their first few months together were tumultuous. When Betsy tried to bathe her, Destiny would wail for her birth mother; in the middle of the night, Destiny would wake up screaming and hurl herself into Betsy’s bed. Betsy, meanwhile, could hardly function in her job. On more occasions than she cares to remember, she broke down crying right before she was due to appear in court for a hearing, and a colleague would have to take over for her.

Over the years, their relationship became easier; by last spring, when the pandemic hit, Destiny was finally thriving in school, a straight-A student. When she told Betsy she was doing homework in her room, Betsy didn’t question her.

From mid-March through late May, Betsy fell into a dreamlike routine. After taking care of her animals and whatever work she had to get done that day, Betsy wandered through the woods and fields surrounding her house, tracking bobcats and watching beavers build their dam in the marsh. She felt gratitude, so much gratitude; for the first time in years, she didn’t feel completely strung out. Then, Destiny’s report card came, filled with Fs, and Betsy lost her shit.

She blamed herself; while she was out in the woods, trying to feel like a whole person again, she said, she was losing control of the situation in the house. She felt guilty, which drove her to try to impose some kind of routine. Destiny responded by refusing to do anything Betsy asked. She would not pick up her room or wear clean clothes. She often reminded Betsy, usually in the midst of an argument over chores, that she wasn’t even her real mother. For months, Betsy teetered on the edge of a total meltdown, feeling like she was doing everything wrong.

Summer 2020

Bree

Bree’s salon reopened in mid-May, but with Niah in remote school five days a week, she still couldn’t go back to work. Then, when summer recess started in June, a friend with a son Niah’s age offered to watch him during the day. With Imaan’s daycare open again, Bree could finally return to the salon.

Because of indoor capacity restrictions, the stylists at O’M were on a staggered schedule, which meant that Bree could only work three days a week. She was earning less than she would have liked, but the unemployment checks — the state benefits, plus the extra $600 weekly supplement from the first federal stimulus package — had given her a cushion, and she felt like she could manage.

Seeing clients again, even in the strangely masked and regulated time of COVID-19, gave Bree energy. “I was never meant to be a stay-at-home mom,” she said. “I need to talk to people. It was so huge for me, mentally, to be able to see my clients again and make them feel good.” After months of being cooped up in their houses, people seemed giddy to return to a semblance of normalcy, and the salon took on sort of a party atmosphere. Especially in those first few weeks, Bree and her clients had a lot to say to each other about how weird their lives had become, and Bree could finally vent to other adults — real, live adults! In person! — about the insanity-making experience of being trapped at home with two kids.

One day, in May, Bree was leaving Roosevelt Park after playing a game of dodgeball with Niah and realized she’d forgotten their ball. She spotted it on the ground, next to a tall, dark, handsome guy. When she went back to get it, she chatted him up. Later, she found him on Facebook and messaged him. She wasn’t looking for anything serious — with two kids, her standards are very high, possibly too high, as her massage therapist has told her, plus, the freaking pandemic! — but she enjoyed the thrill of talking to a whole new human after the brain-fogging sameness of the last few months. For the moment, things were starting to look up.

Sara

At the end of the school year, Sara was furloughed from her job at Mosaic, which came as a huge relief. She had been working practically nonstop for nearly four months, keeping Edith engaged all day and cramming work into nights and weekends.

When the weather got warm enough, Sara took her daughter on day trips to swimming holes all over Vermont. In the morning, she’d pack a cooler full of juice boxes and snacks, and they’d stay out until the late afternoon. “We’d have a blast all day together,” she said. “And then my husband came home, and it fucking sucked.” She would cook nice dinners, or she’d suggest they play a family game or watch a movie, and then none of those things would make her feel any better, she said, because she’d had to be the one to propose them in the first place.

As much as Sara loved spending time with Edith, she had never imagined doing so much of it alone; she was sick of having to come up with every fun idea. The issue, as she saw it, wasn’t that her husband was a bad father or that he didn’t care about Sara’s happiness. The insurmountable problem, Sara felt, was that he did the bare minimum, and he didn’t understand why that wasn’t enough.

As Sara was lying in bed on August 11, the day before her 38th birthday, she promised herself that if she woke up the next morning feeling as awful as she did right then, she’d ask for a divorce. More than anything else, she wanted to stop feeling so resentful all the time, to salvage the possibility of maintaining a decent relationship with the father of their child.

Sara woke up, miserable. That day, they had a family portrait session, and Sara made sure the photographer got photos of just her husband and Edith, and Edith with just Sara. The following day, August 12, she asked her husband to move out.

According to Sara, there was no discussion about whether he would take Edith with him or change his work schedule so that he could spend more time with her during the week. The charge of being the default parent, the one whose bed Edith would crawl into most nights if she woke up scared from a bad dream, fell wordlessly to Sara.

Betsy

By early summer, with the torment of online school in the rearview mirror, tensions had eased between Destiny and Betsy. As part of their unwritten peace treaty, Betsy had all but withdrawn her campaign to get Destiny to pick up after herself. Destiny’s wardrobe had seeded itself all over the house, but Betsy told herself that finding socks in the pantry was preferable to existing in a state of constant nagging.

Destiny’s 10th birthday was in June, and Betsy wanted to do something special for her. On a whim, she booked them a trip to Yellowstone National Park, and they had it practically all to themselves. Destiny, on the whole, was not impressed. She didn’t care about buffalo or geysers; she was apathetic about lounging on floaty mats under the stars in the big thermal pools at their resort. The whole thing, Betsy said, was a suckfest, a parenting fail of epic proportions.

“I can’t tell you how remarkable this is,” Betsy told her, over and over again. “There will never be another time in your life when you’ll be able to hang out in a national park with nobody else around!”

“No!” Destiny would shout back. “You like to be outside! You like nature! This is what you like!”

Fall 2020-Winter 2021

Bree

By fall, most of Bree’s pre-pandemic routines had returned, but in an awkward, piecemeal fashion, creating a set of conditions that sound, on paper, like a deranged SAT word problem.

She can’t work on Wednesdays, when Niah’s school is remote, and she can never work past 4 p.m., when Imaan’s daycare now closes. She isn’t allowed to bring her kids into the salon with her — a new rule since the pandemic — so when the school district calls a snow day, she can’t work at all. Meanwhile, she still has to pay the $80 daily rental fee for her chair in the salon, even when the reason she can’t use it is beyond her control.

“Nobody I work with has children,” Bree said. “You just can’t make someone who doesn’t have kids understand the pressures of being a single parent, let alone during a pandemic.”

In January, Bree dreamed about being hugged. It wasn’t an erotic hug, but a warm, enveloping hug, an embrace that made her feel safe and loved. Around the same time, she dreamed she was engaged. (Hot Park Dad, meanwhile, turned out to be a big disappointment; shortly after Christmas, after months of intermittent Facebook messaging and texting, Bree asked him on a walk — a walk! Nothing more! He never responded.)

Especially this winter, Bree has found herself wishing for a partner or even just a good guy friend, someone who could take the kids sledding or shopping or around the block for an hour, long enough for her to cook without 7,000 interruptions, or to blast gangster rap, or to FaceTime with her best friend, who lives in Arizona. Sometimes, Bree fantasizes about locking herself in the bathroom for 10 minutes, the closest she can get to disappearing, except she knows that as soon as she closes the door, the screaming for Mom will commence.

All day long, everyone wants Bree’s attention. It begins almost the second her kids wake up, sometimes before she’s even had coffee, a barrage of requests and complaints and declarations. Niah needs more whipped cream for his toaster waffles. Imaan has to pee. Niah is getting closer to saving up $100 to buy a new anime action figure, the one with the bendy joints!!!

At the salon, people talk at Bree for hours as she does their hair, their words blending together in one continuous stream of inanities and intimacies. She touches people constantly, responding to their moods and their stories and their needs; some days, she goes home feeling like a wrung-out sponge. “I’m a nurturing person, and I love being a source of comfort,” she said. But the flip side of that, she knows, is that people tend to see her as a bottomless vessel. “Maybe it’s a downfall of mine, but I don’t like to ask for help. I don’t go out there and dump my shit. So then you get pigeonholed. People look at you and assume you’re fine, basically, just because you’re not actively having a nervous breakdown.”

At night, after she’s put the kids to bed, she’ll sometimes zone out in a hot bath, with her scented salt fizzies, and watch several episodes of something mindless on her iPad. Recently, her show of choice has been “Lucifer.” The premise is that Satan has decided that he’s tired of being Satan, which sounds vaguely familiar. (“All he wants is a vacation from being the Dark Lord,” Bree said.)

At night, as she’s trying to fall asleep, the anxious thoughts get louder. She can’t stop thinking in numbers. The rent at her co-op went up this year by $36 a month, and her salon chair rental fee has increased by $5 a day. She’s trying to avoid dipping into her savings so she can afford a down payment on a house, but with less money coming in, her margins are much narrower. Even though things seem to be moving in the right direction, pandemic-wise, she can’t help catastrophizing — because as a single mom, you are the last line of defense in every catastrophe. What if another outbreak forced the salon to shut down again? What if you got sick? What would you do if…? If…? If…?

Betsy

Destiny is now going to school in person five days a week, but the state judiciary system is still operating remotely, which means that all of Betsy’s trials take place via videoconference. Whenever Destiny has a school holiday, or a snow day, or a sick day (because of the school’s COVID-19 policies, Betsy has to keep Destiny home any time she says she isn’t feeling well, even if Betsy knows she’s faking) that coincides with a court day, Betsy has two rules. First, Destiny can pick any floor of the house to occupy while Betsy is in the hearing, as long as she stays on that floor; second, she is not, under any circumstances, to interrupt Betsy, unless it is a real freaking emergency.

Of course, there is always an emergency. Wanting a snack, for instance, is an emergency. Having just come up with a new dance routine can also qualify as an emergency, as can the really cute thing Elmers the cat just did with his paws and might do again, if Betsy would just look! Look! Look! When Betsy hears Destiny coming, she puts out a stiff arm to stop her from Zoom-bombing the trial. She’ll mute herself on the video call, cover her mouth with her free hand — a trick she learned from another lawyer, also a mother, with a small child at home — and hiss through clenched teeth, “Destiny, get away from the computer! I’m in a hearing!”

This year, Betsy is fairly confident that Destiny is doing better in school, though she admits that her assessment is based primarily on a gut feeling and maybe a smidge of self-preservation instinct. Other parents have told her that their kids’ grades have suffered, too, even the kids who were the best students before the pandemic, which comforts Betsy a little.

Every week, Destiny’s teacher sends her home with a written progress report, but Betsy rarely reads it for the same reason that she doesn’t always open her bills on time. It’s not that she doesn’t care; it’s that she cares a lot, too much, and most days, she feels like she’ll explode if she has one more thing to worry about. Recently, Betsy had the anxiety nightmare that Destiny says Betsy always has — that she is an overwhelmed, frightened associate at a large law firm, and she has just been fired. Nobody is allowed to talk to her while she packs up her belongings.

Sara

The first few weeks after her husband moved out were brutal for Sara, the lowest she’d felt in her entire life. He was crashing with friends until he could find a more long-term living situation, and his things sat in the apartment for almost a month — his bureau in what had been their bedroom, the framed photos of his late mother on the walls. Looking at his stuff, she said, made her want to kill herself. She knew, deep down, that she had made the right decision, but she also felt like a failure, as if her value had somehow depreciated because she would forever be trailing a broken marriage. At least once a week, she had panic attacks that jolted her awake, sobbing and hyperventilating, in the middle of the night.

When the school year started in September, Sara went back to her job at Mosaic, but after a few weeks, she realized that was a big mistake. She worked closely with kids who have significant intellectual, physical and emotional challenges; in normal times, this was draining enough, but in the middle of a pandemic, on top of trying to manage her own mental health and raise Edith, it was overwhelming. Given the circumstances, she felt that she could either work five days a week and be a shell of herself, or she could be a fully engaged mother, and she couldn’t deal with the thought of not being a fully engaged mother. She had a small inheritance from her mother, who had passed away less than a year before. She’d saved up some money from being on unemployment while she was furloughed, enough to live on without working full time, and her husband agreed to pay for Edith’s preschool and share the cost of other kid-related expenses.

In October, she lined up a part-time job with Chocolate Thunder Security, which gave her more control over her schedule, and she quit Mosaic. Forthe first time in her life, she started anti-anxiety medication, and the meds, along with weekly therapy sessions and learning how to kickbox, gradually helped steady her. Her husband moved into his brother’s house, an hour from Burlington, and he and Sara settled Edith into a routine. On weekday mornings, Sara drops her off at her preschool in Essex; Edith’s father picks her up after school and brings her back to Sara’s. The three of them will go for a walk with their dog, Hercules, and then they’ll have dinner and maybe play a game of Candy Land, which they rarely did as a family when her husband still lived there. On weekends, Edith goes to stay with her father.

Sometimes, Edith will get a certain look on her face, and Sarah will know she’s missing her dad, she said. They’ll talk it out. “Is it sad that Daddy has to go home? Yeah,” Sara will say to Edith. “But didn’t we just have the best time ever?”

For the past few months, Sara has been keeping Edith home from preschool once a week so they can have an unscripted day together. She’ll make a thermos of hot chocolate and take her sledding at Landry Park in Winooski; if they’re feeling lazy or it’s too cold to go outside, they’ll snuggle on the couch and watch a movie. “I need these days, too,” Sara said. “I need time to actually just enjoy being Edith’s mom.”

Sara can get by on her current income for another month, maybe two, before she’ll have to pick up more Chocolate Thunder shifts or find a second job. The thought of stretching herself thinner, of not being able to hang out with Edith except in the harried mornings and evenings, has been eating away at her.

“If we were a two-parent household, it wouldn’t be an issue,” she said. When she thinks about this, she starts to cry. “I feel really lucky. I have a co-parent who supports me financially, who’s part of our daughter’s life. My situation is amazing, and it still sucks.”