We didn’t initially conceive this story as a race. But if you tell two or more Car and Driver editors that they need to drive from a start line to a finish line, there’s no going back: You’ve officially sanctioned a race. Check the FIA sporting regulations.

The plan was to benchmark the state of EV technology and the nation’s charging infrastructure by road-tripping EVs beyond the range of a single charge. By the time we got to the start line, we had the 11 vehicles from our EV of the Year test staged for a 1000-mile lap through four states, plus a name to prove that what we were about to do was twice as hardcore as the Indy 500: the EV 1000.

We did our best to keep it relatable to you, dear reader, by banning the usual hijinks: no taped-over panel gaps, no stripped interiors to shave weight, no rented U-Hauls to break the wind. The point, we said over and over, was to capture the experience of driving an EV on a long road trip, just as an owner might. Naturally, then, half the teams pumped their tires over the recommended pressure, looking for any advantage that might go unnoticed.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

The drivers—22 total in teams of two—departed from Ann Arbor carrying clues about how seriously they were taking this not-a-race. Staff editor Drew Dorian, driving the Audi e-tron, brought a 50-foot extension cord. Editor-in-chief Sharon Silke Carty packed an acoustic guitar to pass the time while charging the Tesla Model Y Performance. And testing director Dave VanderWerp showed up with two Subway Footlongs. He figured that the Tesla Model S Long Range Plus he was driving would charge faster than any sandwich artist could stack cold cuts, and he wasn’t planning to wait for anyone. In the final moments before the race, VanderWerp’s friend and co-pilot surveyed the competition and quietly observed: “Everyone’s wearing pants. That’s a mistake. All of these people are going to need climate control.”

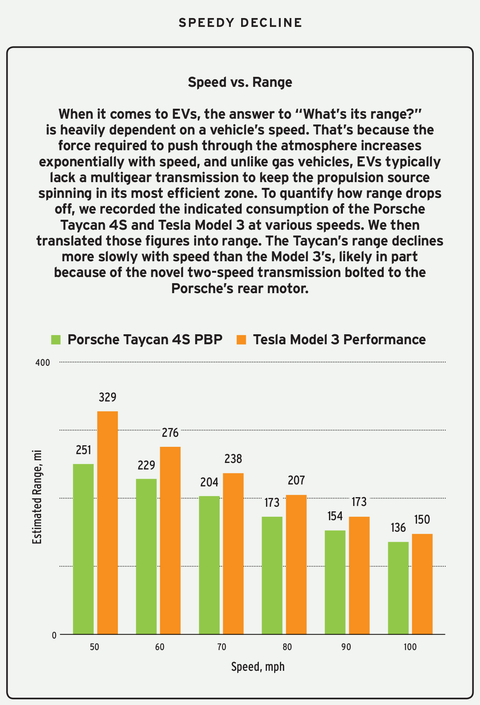

Here’s the thing about racing EVs in the real world: It doesn’t look remotely like what goes on in Monaco or in Daytona or even in the classic Cannonballs. It looks more like racewalking, the Olympic sport where athletes hobble as fast as possible without technically running. The EV 1000 is a contest of endurance and speed, but not too much speed, because to cover big distances quickly in an EV, you have to push the pace while simultaneously holding back.

Any long-distance drive in an EV starts with a question: What are you willing to forgo to maximize your range? Drivers disabled automatic headlights and ignored cruise control. Climate control was used sparingly, if at all. And get this: Speed limits were frequently heeded.

Drivers were free to choose their own route as long as they passed through mandatory waypoints (in order) in Cincinnati; Athens, Ohio; Morgantown, West Virginia; Erie, Pennsylvania; and Ann Arbor. Most teams scouted charging locations ahead of time with A Better Routeplanner (ABRP), an EV-specific navigation website and app. Users provide info about their vehicle and intended speed so ABRP can estimate energy consumption and spit out a route with recommended stops, including the charging time needed at each one, for the fastest possible trip. At least that’s the theory.

User error almost certainly played a role, but the drivers in the Nissan Leaf insist they were following the app’s guidance when they made the first pit stop—charging for all of six minutes—just 23 miles into the race. That mistake came back to haunt them when they were the last of four teams to arrive at a single ChargePoint DC fast-charger at an adult-education center near Lima, Ohio. The day’s lesson: Be wary of any fast-charging station with only one unit. The Leaf squeezed electrons from a nearby lower-power Level 2 plug for 96 minutes before the fast-charger became available. The Nissan team would have been waiting longer, but the duo in the Audi had given up their spot to search for another charging station, only to return a short while later. The unit they’d hoped to use was broken.

The teams in the Tesla Model 3 and Model Y had it comparatively easy. While Tesla’s built-in nav can’t plot a multistop journey, setting the next waypoint directed them to fast and reliable Superchargers as necessary. Three non-Tesla teams also kept the pace based on a simple but smart strategy: Because an EV’s battery replenishes faster at a lower state of charge, ideally you wait until the vehicle is nearly out of juice to plug in. The Kia Niro EV and Volkswagen ID.4 made it to a Dayton suburb for their first stops, and the Ford Mustang Mach-E went 237 miles to the edge of Cincinnati before it had to charge.

VanderWerp, in the Model S, wanted to post a big number on the first leg to make a statement. Possibly that statement was “No owner would ever do this.” To maximize the energy available for moving the car, he ran a radar detector off a portable battery and played music through a Bluetooth speaker. With climate control off, the cabin temperature reached 86 degrees despite a 65-degree ambient temperature. At least all the sweating meant that neither VanderWerp nor his partner needed the TravelJohn disposable urinals they’d brought. They plugged into their first Supercharger after 326 miles and were back on the road 26 minutes later.

As they skirted Cincinnati, the eight teams without access to Superchargers had decisions to make. The southern leg of the route pulled drivers off the interstate and onto two-lane highways with few fast-charging opportunities. Teams could take the relatively straight shot from Cincy to Athens, where a single 50-kW unit waited, or they could detour northeast to Columbus, adding 27 miles to the trip but also passing an Electrify America station good for up to 350 kilowatts.

Several drivers had, by this point, abandoned their prescribed plan from ABRP and instead used the PlugShare app and their own judgment to select stops. Trying to figure out how long to charge and whether you need to slow down to make your next destination requires constant calculation. Executive editor Ryan White pointed out another possible reason why Americans have been slow to adopt electric vehicles: As a people, we hate math.

In the southeast sector of our racetrack, charging options were abysmal. Seven of the eight non-Tesla EVs ended up charging in Athens, including a couple that had stopped in Columbus too. Once again, cars stacked up waiting for a single ChargePoint DC fast-charger.

In the spirit of driving as an owner might, teams were required to stop from midnight to 8:00 a.m. In Morgantown, the approaching dark period started a race within a race to claim the few plugs in the city. The Volvo XC40 Recharge scored the prime spot at a Harley-Davidson dealer next to a hotel. The Niro team found a free Level 2 station in a permit-only parking lot, figured that the charging cord locked into the port would prevent anyone from towing the car, and walked a quarter-mile to their hotel. The Audi drivers used Uber to shuttle between their charging car and a hotel. The Polestar 2, with less than 25 percent battery remaining, was left unplugged all night.

About 50 miles north of Morgantown, the Mach-E’s fast start was falling apart in a spectacular string of charging failures. An EVgo station refused to work for more than a minute at a time, eating up a half-hour before the drivers moved on. With 6 percent battery charge, the Mach-E crawled 10 miles to another EVgo unit and had the same problem. The team then crossed the street and hooked up to a Level 2 station.

Yeah, watching paint dry is boring, but have you ever watched an electric car charge? The Mach-E added 12 miles of range in 50 minutes, which is exactly how long the drivers’ patience lasted. With the car showing just 24 miles of predicted range, the Mach-E team gambled on making it to the Electrify America location 30 miles away.

Climbing the energy-sapping hills surrounding Pittsburgh, the Ford began projecting its own range anxiety onto the occupants. First, the car told the driver to find a different, closer charging station. Then it warned that the car wouldn’t make it to any public charging station, and the pop-up message advised the driver to find any available outlet to plug into. Finally, the computer gave in to despair and told the driver to pull over.

The driver (the author of this tale) kept his foot in it—at least enough to hold 50 mph on a 55-mph highway—and arrived at the Electrify America station with the instrument cluster showing zero range and no battery charge. For the drivers, the moment of relief was soon eclipsed by the disappointing realization that, having squandered nearly two hours, they had also lost any chance of beating a Tesla.

The Model 3 and Model Y ended the day at the same hotel in northeastern Ohio. Technical editor David Beard, who drove the Porsche Taycan 4S like he’d entered the original Cannonball, made it to Pittsburgh, with the VW close behind. The Model S held a commanding lead, stopping in Sandusky, Ohio, just 114 miles from the finish line. The Nissan Leaf spent the night back in Athens, less than halfway through the 1000 miles.

Life got easier as the teams reached Pittsburgh, having returned to the interstate, where fast-chargers are spaced at regular intervals. Our drivers were also becoming savvier. Several teams developed a fierce loyalty to the Electrify America network. Funded by Volkswagen as penance for selling and lying about dirty diesels, Electrify America has built more than 600 stations with 2600 plugs since 2017, and it’s now the closest thing to a competitor to Tesla’s fast-charger network. The company typically installs the equipment in banks of four to 10, which means there are options if units are broken or occupied.

But not for our teams in the Polestar 2 and Volvo XC40 Recharge. Electrify America equipment is made by four companies, and charging stations from one of them were incompatible with the Polestar and Volvo at the time of our drive. (Both automakers say software updates have since fixed the issue.) Deputy creative director Nathan Schroeder, piloting the 2, had been tipped off ahead of time, and he called EA’s customer service to ask which units along the route would and wouldn’t work. But something got lost in translation. Charging units that weren’t supposed to work did, and those that were supposed to didn’t, adding an element of chance to an equation that didn’t need any more variables.

Teslas are generally immune to such nonsense. While Superchargers could be finicky in their early days, the current equipment is more dependable than a gas-pump credit-card reader. The network is also dense. The Model S once passed four Supercharger stations before stopping. It arrived back at the office after 16 hours and 14 minutes of driving and charging. Google Maps says this trip is just 50 minutes shorter without a single stop.

Carty and staff editor Austin Irwin pulled into their last charging stop after the Model 3, but they refused to accept third place. When the other team wasn’t paying attention, they unplugged the Model Y and took off at a furious pace, beating the 3 back to the office to claim second.

Tesla’s sweep of the podium makes it clear: If you want to regularly drive long distances in an EV today, you’ll want a car with access to Tesla’s proprietary charging infrastructure. The rest of the group trickled in over the next several hours, with the exception of the Leaf, which needed twice as long as the Tesla Model S to finish. With its short range and slow charging, the Nissan clearly wasn’t intended to stray far from home.

Our drivers are split when asked whether the EV 1000 was harder or easier than expected, but most say that if they were to do the trip again, they would do one thing differently: drive a gas car. And that includes the Tesla drivers. We’ll know that the charging networks and EV technology are fully baked when we’re no longer saying that.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io